Gifts, Talents, and Hard, Guided Work (Also, Aikido, VCFA, and Writing YA) by Dean Gloster

I’ve

been fortunate, in my new career as a novelist, not to be an especially gifted writer.

I’m good with

that. It means I have to struggle, to work hard, to consciously grow and to improve

in some areas if I’m going to keep writing. Which is as it should be.

(Portrait of the Artists, as a Young Hand)

I mostly don’t

believe in “Gifts” and “Talents” with capital letters, which by themselves can

shape someone into a Great Artist in a creative arena.

Oh,

there are amazing writers creating amazing works, but the more I talk to them

about their process (“It took twenty-eight drafts, and I wasn’t sure I really

had something until draft twenty-six…”) it sounds more like the product of

hard, fierce work over a long time.

Even the outliers,

the absolute bursts of inspiration (“The picture book came out almost complete,

and when I sent it to my agent, she said she’d send it out without changing a

word”) have—in my experience, anyway—happened only to the hardest-working and

most steadily productive writers I know. (*Cough* Merriam Saunders.)

If you want to be

struck by lightning, it turns out, you need to spend lots of time outside, uncomfortably wet, on high ground, during

thunderstorms.

I do believe in

smaller things, though—aptitudes. If you’re smart and analytical, for instance,

that may help you learn faster in an area that requires lots of sub-skills

(such as, say, writing novels.) Having lots of endurance also helps with things

that take sustained effort over time, like novel-writing. If you are resilient,

you can more successfully weather the setbacks of rejection that are part of

the process.

Me? As a writer, I

have an aptitude for dialogue and voice. Description of setting, explicit

point-of-view character emotion? Not so much. So I know some of what I need to

work on.

But the truth is,

if you work hard, you can improve even at things you don’t have much aptitude

for, so long as you have passion for them.

Last year, in my fifties,

after a particularly unfortunate U.S. presidential election, I took up the

study of Aikido.

Aikido is a

wonderful discipline. To oversimplify and perhaps miss the point completely—as

we enthusiastic white belts are uniquely positioned to do—Aikido is a martial

art that allows one to throw, immobilize, and pin attackers while doing the

least amount of damage. It involves balance, mindfulness, blending with the

attack, flow, relaxed shoulders, and a combination of footwork and moving one’s

torso—not just arms—in a wide range of what seem to a beginners extremely

precise techniques.

It’s a martial art

I’m almost spectacularly exactly unsuited for.

I have limited

forward flexibility, but there are lots

of forward rolls involved, as ten-year-olds throw me onto the mat. I have a

PTSD-heightened fight-or-flight reflex (without, in my case, much flight

component) but Aikido involves relaxed shoulders and flow and grace, not

tensing, even when a black belt simulates a punch to my face. I’m a concrete,

analytical guy, and there is a ki

energy flow aspect to Aikido that doesn’t translate exactly into those terms. And

I’m really aggressive and somewhat athletic, so my go-to approach is to add more—a lunge, an oomph, a little body

English lifting my back foot as part of the throw—which is exactly, precisely not Aikido.

Part of the reason

I love Aikido, though, is that it almost completely challenges me and who I am,

and asks me to learn a profoundly new approach. It doesn’t speak to my pre-existing

strengths or the gifts and aptitudes I bring from my first fifty-some years,

but asks me to develop some new ones.

That rocks.

The best way to

progress in anything—writing, Aikido, or anything else—is to get some coaching.

Practicing hitting a golf ball 10,000 times wrong doesn’t do you much good.

Getting guidance on how to hit it better, and then practicing that, does.

So, when I

was in my fifties, while my first novel was under submission, I also went back to

school, at Vermont College of Fine Arts, to get an MFA in writing for children

and young adults.

The

faculty, it turned out, was amazingly talented. My classmates, it turned out,

were also amazing and talented. There were writers who were much, much further

along their writing journey and more accomplished than I was. (*Cough* Ally

Condie.)

There

were writers less than half my age who were more than twice as talented as I

was. (*Cough* Marianne Murphy.)

There

were writers who were so amazing even at the things I did best—voice, humor,

blending humor with serious topics—that I would have been intimidated to read

their novels before mine came out. (*Cough* Addriene Kisner. Buy. Her. Book. Out this spring.)

And

that, friends, is one difference between almost all of us who write for young

people and some of those who don’t: The brilliance of my classmates does not

diminish me. We’re on the same side. We believe in the magic of books for young

people, because we experienced that magic, as young people.

I

have come full circle. I believe somewhat in talent. I believe somewhat in

gifts. But I believe more in hard work and in practicing a discipline and in

improving. My job, these days, is to get better. It’s exciting and it’s fun. I'm a very lucky guy.

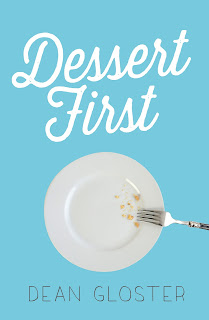

Dean Gloster graduated with an MFA in

writing for children and young adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts in July

2017. He is a former stand-up comedian and a former law clerk at the U.S.

Supreme Court. His debut YA novel DESSERT FIRST is out now from Merit Press/Simon Pulse. School Library Journal called it “a sweet,

sorrowful, and simply divine debut novel that teens will be sinking their teeth

into. This wonderful story…will be a hit with fans of John Green's The Fault in Our Stars

and Jesse Andrews's Me and Earl and the

Dying Girl.” They are remarkably patient with him at the wonderful dojo Aikido

Shusekai in Berkeley, California.

I am so with you on this. I, too, believe more in hard work.

ReplyDeleteI was the hiring chair at my old law firm for a few years and always looked for signs of hard work on resumes more than anything else. Agree! But basketball, not Aikido. We also are all about balance ... and attack. :-)

ReplyDeleteGreat post, Dean! Thank you.

ReplyDelete