Distrust Your Darlings But Don't Delete Your Words Due to Bullies by Dean Gloster

This

month’s topic is editing—editing yourself and being edited. I have thoughts on

both, which, these days, boils down to: be a brave, canny protagonist (in my view, good

advice for life generally.)

For editing

yourself, the most commonly misunderstood piece of advice is “kill your

darlings”—that is, delete that wonderful descriptions, joke, piece of dialogue,

or stellar chunk of prose that you are inordinately proud of, but which stands

out, and doesn’t quite serve your story.

Seriously.

The standard advice is to delete your very best stuff, when it doesn’t belong.

As is often the case, the most memorable and compelling phrasing of this

writing adage is by Stephen King: “Kill your darlings, kill your darlings, even

if it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.”

For the

most part, that’s good advice, if a little extreme. Mike Schur, a

writer for The Simpsons, said in an interview that often they cut the very best

joke in every episode, which never made it to the final script, because that

joke didn’t serve the story—it didn’t move things forward.

And the

advice is--unfortunately--often necessary. We all resist prying these gems out of our

manuscripts, even when our critique partners, writers’ groups, or even editors

tell us they ought to go. Yes, it doesn’t really sound like something a

16-year-old girl would say. But it’s so good. Sigh. Cut it.

But it’s

advice that’s also overstated. Sometimes, those passages with brief flashes of

playful lyricism are what makes the book a delight to read. And as we’re

writing the story, we don’t always know what, at the end of the day, will

really belong. And not every 16-year-old girl sounds the same.

So, if you

do have a gem, a darling, instead of just deleting it, carefully copy it into a

separate document (I call mine snips) in case it needs to come back later, when

you realize it really does serve the story. That does make it a little easier

to pry out of the current draft.

A more

accurate and nuanced—but less pithy—rendition of this self-editing adage is: Be

deeply suspicious of your darlings and (usually) relocate them—out of the

manuscript.

My advice about letting certain other people edit us at this moment is far less nuanced:

Don’t let authoritarians and their enablers shut us up. Or cause us to silence ourselves.

This week,

Presidential candidate Donald Trump stomped all over various veterans’ graves

at Arlington National Cemetery, with photographers in tow, to create digital

campaign ads, in violation of both basic decency and federal law, 32 CFR

553.32(c), which provides “Memorial services and ceremonies…will not include

partisan political activities.”

In the

process, a member of Trump’s entourage assaulted a woman who, in the course of

her job at Arlington National Cemetery, tried to stop them. She promptly filed

a complaint, summoning officers, but chose not to file charges for assault

because “she was afraid that she was going to be retaliated against by Trump's

supporters.” An entirely reasonable fear, it turns out, because in the

meantime, Trump’s campaign spokesperson Steven Cheung had publicly accused her

of having “a mental health episode” for doing her job—an attack so over-the-top

that the U.S. Army responded with an unprecedented rebuke, that it was

unfortunate that she “and her professionalism had been unfairly attacked.”

I

understand the worker’s reluctance to become a victim of retaliation. But I

would urge all of us—especially writers—to be protagonists instead and to stand

against this rising tide of pro-authoritarian bullying. Those of you who’ve

read my posts here won’t be surprised to learn I am somewhat political online. (Understatement

alert.) I have a Twitter account with 142,000 followers, and occasionally what

I post there goes viral and triggers a response from the kind of people who

would bully that cemetery worker, enough so that they (rarely, but still) send

me soft-serve death threats in the replies:

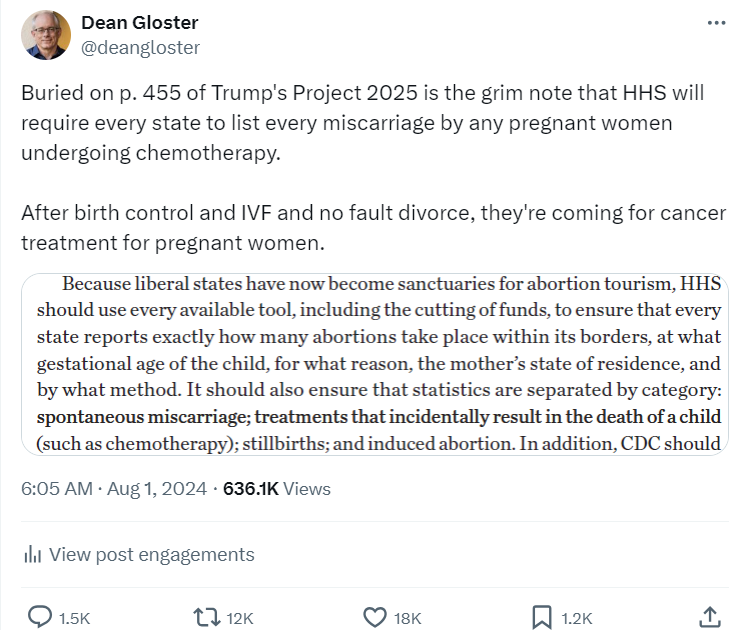

One tweet I

sent recently:

Brought the immediate response of the following one-star review of my YA novel Dessert First,

worded so that I’d know exactly what had triggered it (and, presumably, so I would

mute my future similar social media posts to avoid this kind of retaliation

review):

It was, in fairness, a credible parody of my tweet. I reported it to Amazon anyway, and—while it’s still up as the latest review of my book—it apparently isn’t being used anymore to calculated the average number of stars for customer reviews. And, dear readers, I have not muted--and will not mute--my social media posts.

So yes—if

we write books the are inclusive, diverse, kind, honest, authentic, and open-hearted

enough to touch readers and make them feel seen, we may suffer consequences like

having our books banned in parts of Texas, Florida, and Missouri. Or getting nasty reviews. But I think

that means we should write more of those books, because our

readers need more of them. And we should also use our voices to speak out in favor

of democracy and decency, while we can. Many of us have platforms on social

media, and, as writers for young people, our platforms should be used for more

than ritual adverb sacrifices.

There may

come a time when, as writers, we are silenced. But we should not silence

ourselves before that curtain falls. And if we speak out enough now, we might even

prevent that from happening. That’s my choice, anyway.

Be brave, friends. Be a protagonist. And good luck to us all.

Margaret Atwood, demonstrating that it’s difficult to burn the fireproof version of her book

! Be a protagonist.

ReplyDeleteGo, you!

ReplyDeleteWell said! I pillory both Trump and our former governor who tried to imitate him, but was too stupid (in Maine) often in stories.

ReplyDelete